A woman voting in the 2016 Ghana election. (Photo: USAID)

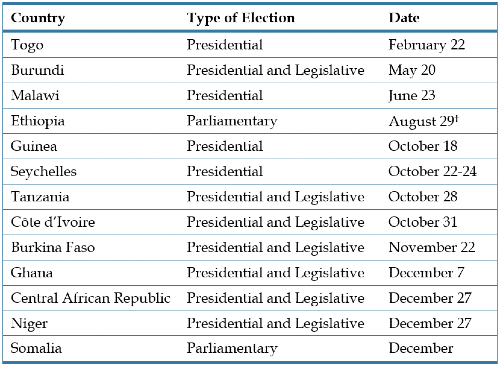

As Africa gets set to host a dozen presidential or general elections in 2020, leaders seeking to evade term limits, democratic resiliency in the face of armed conflict, and the increasingly overt efforts by external actors to shape outcomes emerge as recurring themes.

2020, thus, represents an important benchmark of whether African citizens (especially its increasingly active and networked youth), regional organizations, and international partners will tolerate efforts to erode democratic norms—or whether a renewed effort to uphold certain standards will gain traction.

Underscoring the stakes at play, a majority of African elections in 2020 will be held in countries confronting or emerging from conflict, including Burkina Faso, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Niger, and Somalia. These countries face crises sparked from previous exclusive power structures, militant Islamist insurgencies, and the challenges of building inclusive national visions from polarized polities. Consequently, the strong link between governance and security in Africa will be on full display in 2020.

Africa’s 2020 elections are clustered in West Africa (with 6 elections), the Horn (Ethiopia and Somalia), and the Great Lakes (Burundi and Tanzania). Ten of the 13 elections are scheduled for the latter half of the year. This suggests that 2020 will be a dynamic period of maneuvering by key actors seeking to advance not only their individual interests, but also their vision for the future of their countries—and governance norms for the continent as a whole. Here are some of the key issues to watch:

Togo

Togo

Presidential Election, February 22

The headline of Togo’s presidential elections is President Faure Gnassingbé’s efforts to stay in power for a fourth term—and extending the hold his family has had on the presidency since 1967. Faure Gnassingbé took office in 2005 in a disputed election following the death of his father, Gnassingbé Eyadema, who had ruled the small West African country with an iron fist for 38 years.

Following 2 years of sustained popular protests demanding that Faure Gnassingbé step down at the end of this term, a two-term presidential limit was restored to the Constitution in 2019. (In 2002, Gnassingbé Eyadema was able to strike term limits from the Constitution). However, the ruling Union of the Republic party, which holds 59 of 91 seats in Parliament, did not apply the new term limits retroactively, effectively resetting the term limit “clock” and opening the door for Faure Gnassingbé to run for a fourth term in 2020 and possibly a fifth term in 2025.

Togo’s electoral playing field is unbalanced, with the Independent National Electoral Commission, judiciary, and state media led by loyalists to Faure Gnassingbé. Most importantly, the military is highly politicized and has been a close governing partner with the ruling party for decades. Faure Gnassingbé’s Kabye ethnic group comprises 70 percent of the army, though it makes up only a quarter of the population.

Togolese protesters before police in Lomé in 2017. (Photo: VOA/Kayi Lawson)

Togo’s notoriously fragmented opposition parties, supported by an energized diaspora, have been increasingly adamant in demanding an end to Togo’s dynastic rule and a transition to democracy. They showed unprecedented levels of organization and resiliency in coordinating the protests that led to the reinstatement of term limits. Tellingly, however, the C-14 coalition of opposition parties that led the protests effectively disbanded once the term-limit reform was passed. Instead, the parties will run multiple candidates, potentially paving the way for Faure Gnassingbé to win a first round electoral victory.

This is not a foregone conclusion, however. One of the candidates, Jean-Pierre Fabre of the National Alliance for Change, garnered 35 percent of the votes in the 2015 presidential election, reflecting a strong base of support. Moreover, many members of the C-14 have rallied behind former Prime Minister Agbéyomé Kodjo, who has been selected as the candidate of the Democratic Forces, a coalition initiated by Philippe Fanoko Kossi Kpodzro, Archbishop Emeritus of Lomé. Should the election go to a second round and the opposition join forces, they would have a strong chance of winning a majority of votes.

With high levels of popular discontent over the lack of political freedom and Togo’s economic malaise, there is a groundswell of support for a long-delayed transition to democracy. The issue to watch will be whether the opposition can become sufficiently organized to offer a united front to overcome Faure Gnassingbé’s influence on the electoral process. It will also be worth keeping an eye on the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). In the past, the regional body has been a leading force in upholding democratic norms in the region (most recently by facilitating the departure of Yahya Jammeh after he was defeated at the ballot box in 2017), greatly elevating ECOWAS’s reputation. However, ECOWAS has been notably passive in responding to Togo’s persistent democratic deficit.

Burundi

Burundi

Presidential and Legislative Elections, May 20

Burundi’s elections take place in the long shadow of the country’s 2015 elections when President Pierre Nkurunziza, already in power for 10 years, defied the constitution’s two-term limit to seek a third term. This reversed a period of multiethnic peacebuilding that had been in motion since the signing of the Arusha Accords in 2000 ending the Burundian civil war in which 400,000 people perished. Nkurunziza’s move to extend his time in power set off widespread protests, which were violently suppressed. Subsequently, most of the country’s political opposition, civil society leaders, and independent media fled the country or have been imprisoned, tortured, or murdered.

The political crisis has also led to the fragmentation of the security sector. Many officers who refused to participate in the crackdown have also fled the country or joined armed opposition groups. Intimidation from Burundi’s police and youth militia, the Imbonerakure, who act in support of the ruling CNDD-FDD party, continue to characterize the political environment. Progress made toward military professionalism between 2000 and 2015 has been largely reversed, with the armed forces increasingly polarized along ethnic and political lines.

Burundian soldiers dispersing protesters in Bujumbura in 2015. (Photo: AP/Jerome Delay)

An estimated 2,000 people have been killed, and nearly 500,000—out of the total population of 11 million—have become refugees or internally displaced since 2015. A 2019 UN Commission of Inquiry on Burundi investigation found that the eight common risk factors for atrocity crimes are all present in Burundi.

In this fraught climate, a controversial 2018 referendum extended presidential terms from 5 to 7 years and opened the door for Nkurunziza to run for a fourth term in 2020 and a fifth term in 2027. The CNDD-FDD, however, has picked its Secretary General and hardline Interior Minister, General Evariste Ndayishimiye, to contest the upcoming elections. Meanwhile, Nkurunziza has been given the titles of “Eternal Supreme Guide” and “Paramount Leader” in legislation approved in January 2020. This unelected role will enable Nkurunziza to remain the dominant political force in Burundi, but with even fewer constraints.

In short, having failed to stop Nkurunziza’s violation of term limits in 2015, Burundi is in the throes of a self-inflicted political crisis with grave humanitarian consequences that shows no signs of abating. This crisis, in turn, has the potential to trigger more widespread instability in the broader Great Lakes region involving Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, and Uganda.

Malawi

Malawi

Presidential Election, June 23

The rerun of Malawi’s presidential election will take place on June 23 following the historic ruling by Malawi’s Constitutional Court overturning last year’s presidential election results. Official results from the May 2019 poll showed President Peter Mutharika winning a second term with 38.6 percent of the vote. Lazarus Chakwera of the Malawi Congress Party (MCP) garnered 35.4 percent, and Vice President and leader of the United Transformation Movement Party (UTM) Saulos Chilima came in third with 20.2 percent.

However, the Constitutional Court’s ruling cited widespread irregularities, including duplicate forms and the use of Tippex correction fluid and missing signatures on some result sheets. The Court ordered Parliament to pass new electoral laws in order to hold fresh elections, including the shift from a single round plurality electoral system to a 50 percent+1 majority system. The Court also ordered Parliament to assess the competency of the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC), leading to the resignation of the MEC chairperson viewed as a Mutharika loyalist.

While Mutharika has attempted to sidestep the Constitutional Court decisions, on May 8, 2020, the Supreme Court rejected Mutharika’s appeal and unanimously upheld the Constitutional Court’s ruling, paving the way for the fresh elections. Only presidential candidates who participated in the nullified May 2019 elections will be allowed to run.

Malawi’s replayed presidential election is set to be highly competitive. Mutharika and his ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) have formed an alliance with opposition party, United Democratic Front (UDF), in an effort to reach the 50+1 majority. Likewise, the second and third runners-up from the May 2019 election, Chakwera and Chilima will run against the DPP-UDF alliance.

Malawi’s democratic institutions have shown remarkable independence in pressing for a transparent tally for this election cycle and by resisting Mutharika’s attempts to subvert executive oversight. As a result, Malawi’s 2020 presidential election do-over will be highly consequential, not only for choosing Malawi’s president for the next 5 years, but for upholding democratic standards in the region and across the continent.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Parliamentary Election, August 29 (Postponed due to coronavirus)

One of the most intriguing and consequential elections of the year will be in Ethiopia in what is effectively shaping up to be the first competitive democratic election in this country of 100 million people. The prospect for such a historic moment has been shepherded by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who upon taking the mantle of the premiership in April 2018, has opened up Ethiopia’s erstwhile tightly controlled political system. Under Abiy, the government has released hundreds of political prisoners, eased restrictions on independent media, lifted bans on 264 websites and television networks, and confirmed formerly exiled opposition leader, Birtukan Mideksa, as the head of the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE).

Tempering the excitement of the elections is the realization that neither the state nor the population has undertaken such a genuinely competitive process before. Consequently, there are many open questions regarding electoral rules and how political actors and citizens will engage in this process. Some of these questions include: Will the newly empowered NEBE will be able to effectively administer the election and be perceived as fair? How will political leaders respond if electoral results do not match their expectations? Will political parties pursue their appeals through designated legal channels? Will the justice sector be perceived as an evenhanded arbiter? How capable will security forces be in responding to any threats of violence? Will winners pursue national or parochial interests once in office? Will all sides realize that losing an election in a democracy does not mean that one is relegated to oblivion, but rather that it has experienced a temporary setback and an opportunity to continue to rally more supporters to its position?

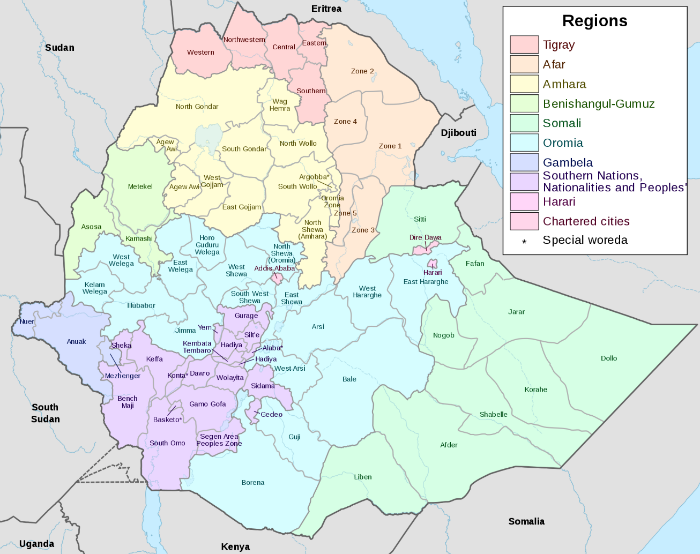

A map of the regions and zones of Ethiopia. (Image: NordNordWest)

The issue of ethnicity is infused into all aspects of the electoral process. Ever since Ethiopia adopted a political structure of ethnic federalism in its 1992 Constitution, fundamental questions of national versus ethnic identity have taken on greater prominence. Ethnically based perceptions of power and entitlement have been building since and have led to a growing toll of violence from ethnic militias in recent years. This has resulted in hundreds of reported deaths and an estimated 2.8 million displaced. Now that competitive elections are on the horizon, the centrifugal forces of ethnicity are likely to be amplified further. Barring motivations to remain part of a unified national vision, regionally based politicians will have strong incentives to appeal to ethnic nationalist tropes in order to mobilize supporters. This is likely to be highly divisive and potentially explosive.

To avoid this trajectory, leadership from across Ethiopia’s political parties and regions will need to commit to a national narrative and denounce violence, regardless of the short-term gains it may seem to bring. Some efforts to build cross-ethnic and cross-regional coalitions have begun. To the extent that these gain traction, parties and political actors will have incentives to advance unifying themes. Otherwise, Ethiopia faces the risk of a series of fragmented jurisdictions with no common rationale. With over 100 political parties, the mechanisms for articulating national policies while building grassroots networks remain rudimentary.

Given its long, celebrated history of shared culture, traditions, and civilization, Ethiopia is starting this transition from a stronger foundation than many other African countries. As with any transition, before new norms and institutions can be established, the example set by leaders will be enormously influential. A key question for Ethiopia in this historic election, therefore, will be how well its political and civic leaders rise to the occasion.

Guinea

Guinea

Presidential Election, October 18

Legislative Elections and Constitutional Referendum, March 22

The dominant issue in Guinea’s 2020 presidential election is 81-year-old President Alpha Condé’s effort to seek a constitutionally prohibited third presidential term. A longtime opposition candidate, Condé became Guinea’s first democratically elected president in 2010 following Guinea’s improbable shift toward democracy after decades of military government. Rather than paving the way for a peaceful transition, however, Condé has advanced a constitutional referendum to be held March 22 that proposes an amendment to extend presidential terms from 5 years to 6. The expectation is that Condé would use any such amendment as a pretext to justify a bid for a third term. Another major change proposes that the president of the Constitutional Court will no longer be elected by its members, but instead will be directly appointed by the president. This will strengthen the executive branch’s grip on Guinea’s Constitutional Court, further eroding its impartiality.

The holding of the referendum is itself controversial since typically this would need the approval of the full National Assembly. However, in this case, approval for the referendum was granted solely by the speaker of the National Assembly. The referendum will be coupled with the long-delayed legislative elections on March 22.

The primary force opposing Condé’s bid to extend his time in power is Guinea’s civil society. Civil society organizations have repeatedly organized protests to rally opposition to any constitutional changes regarding term limits. The police have at times responded to the protests with force, resulting in at least 36 civilian deaths since October 2019. On December 10, 2019, an estimated 1 million protesters took to the streets. Since then, demonstrations have continued in the tens of thousands.

Civil society organizations have repeatedly organized protests to rally opposition to any constitutional changes regarding term limits.

Opponents contend that Condé has increasingly governed in an authoritarian manner. In addition to attempts to suppress protests, Condé’s 2015 electoral victory was marred by widespread irregularities. Opponents believe the outcome was facilitated by Condé’s stacking of the Independent National Electoral Commission with loyalists. Many Guineans are also angered that Condé has failed to hold accountable security actors responsible for the September 2009 stadium massacre of 150 protesters and systematic rape of dozens of women perpetuated during the rule of coup leader Moussa Dadis Camara—a defining event in modern Guinean history.

Another factor in Guinea’s 2020 election will be Russia’s explicit effort to support Condé’s bid for a third term. In a televised New Year’s Eve address, Russia’s then-ambassador to Guinea, Alexander Bregadze, condoned the constitutional change telling Guineans that they would be “mad” to allow the “legendary” Condé to step down. Guinea holds the world’s largest reserves of bauxite, the ore used to produce aluminum. Russia’s biggest aluminum company, Rusal, owns a major bauxite mine in Guinea and gets a quarter of its bauxite from the country.

Seychelles

Seychelles

Presidential Election, October 22-24

The Seychelles is expected to continue its steady strengthening of democratic institutions with the holding of presidential elections in October. While there are 12 registered political parties, the race is anticipated to come down to incumbent President Danny Faure of the United Seychelles party, who is seeking a second term, and Wavel Ramkalawan of the Linyon Demokratik Seselwa party, which controls a majority in the National Assembly.

This year’s elections are expected to benefit from the December 2018 creation of a permanent chief electoral officer to oversee the Electoral Commission secretariat and its operations. This official will be responsible for preparations, logistical support, and hiring and training of electoral staff. This arrangement, moreover, is expected to further ensure the separation of responsibilities between the oversight and the implementation tasks of the Electoral Commission.

The Seychelles has played a valuable role within Africa’s peace and security architecture through its interdiction and prosecution of transnational crimes committed on the western Indian Ocean, primarily piracy and narcotics trafficking. The Seychelles is expected to continue to fill this role regardless of which candidate wins the presidency.

Tanzania

Tanzania

Presidential and Legislative Elections, October 28

Since President John Magufuli came into office in 2015, democratic space has diminished more rapidly in Tanzania than in virtually any other African country. Once seen as a budding democracy with a widely admired respect for civil liberties, Tanzania now has a government that cracks down on independent media, opposition parties, and human rights defenders. In February 2016, Magufuli stated that he would see to it that there would be no opposition political parties by the next general elections. His actions since then seem aimed at realizing precisely that goal.

Political activities such as public meetings, rallies, and demonstrations organized by opposition parties have been banned. Legislation passed in January 2019 gives a state-appointed registrar sweeping powers over internal political party matters. Opposition leaders say the legislative changes would effectively criminalize political activity. In fact, two of the country’s largest opposition parties, CHADEMA and ACT-Wazalendo, have since been threatened with deregistration. Although the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party has held power continuously since independence in 1961, Tanzania now risks officially reverting to a one-party state after 28 years of multiparty politics. The consequences from this, especially in Zanzibar where there is a long legacy of distrust toward the ruling party, could be particularly destabilizing.

The key concern will be less about the policies and visions of the respective parties than whether the exercise will be sufficiently credible to be considered an election at all.

Draconian cybercrime laws, intimidation of journalists, and the silencing of opposition newspapers and bloggers caused Tanzania to drop 40 places on the Reporters Without Borders annual Press Freedom Index. Moreover, given Tanzania’s highly centralized political structure, Magufuli directly appoints all key government positions, from district commissioners to judges.

In short, as Magufuli seeks a second term in 2020, the key concern will be less about the policies and visions of the respective parties than whether the exercise will be sufficiently credible to be considered an election at all. This, coupled with independent polling that shows Magufuli’s popularity has fallen precipitously since taking office, means any Magufuli victory will be heavily tainted and lacking in legitimacy. The degree to which the African Union and international partners are willing to recognize such an outcome in Tanzania will, in turn, have implications for governance norms elsewhere on the continent.

Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire

Presidential and Legislative Elections, October 31

A challenge to uphold presidential term limits coupled with unresolved tensions surrounding Côte d’Ivoire’s civil war in 2010 make the 2020 elections a watershed for the country. The outcome of these competing forces will determine whether Côte d’Ivoire continues on the path of political reform and economic growth (which, at 7 percent per year, is among the highest in Africa) or lurches back to a form of unaccountable exclusionary governance that triggered the 2003 and 2010 civil conflicts.

President Alassane Ouattara. (Photo: s_t)

President Alassane Ouattara, who has led the country’s post-war rejuvenation, completes his second term in 2020. However, the 78-year-old Ouattara has claimed that a new constitution adopted in 2016 has reset the term-limit clock and that he may indeed run for a third term. According to Afrobarometer polling, 86 percent of citizens support a two-term limit in Côte d’Ivoire.

Ouattara has also demonstrated increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Since the start of 2019, there have been 14 arrests of activists and opposition members. Most prominent was the warrant for the arrest of former close ally and leader of the National Assembly, Guillaume Soro, after Soro declared his intention to run in the 2020 elections during a European tour in December 2019. Soro was subsequently forced to divert his flight back to Abidjan to avoid being arrested. The charges against him are widely seen as politically motivated.

Similarly, opposition figure Nathalie Yamb of the Lider party was expelled from Côte d’Ivoire in December 2019 after suggesting France exerted undue influence over the Ouattara government. In October 2019, Jacques Mangoua, a leading figure in the opposition Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire–African Democratic Rally (PDCI–RDA), was arrested for allegedly possessing weapons at his home. Subsequently, he was sentenced to 5 years in prison. In January 2019, Alain Lobognan, a parliamentarian close to Soro, was arrested and sentenced to a year in jail and fined about $520 for posting a “fake news tweet.”

The 2020 electoral process in Côte d’Ivoire will be a test of the country’s capacity to assert constraints on the executive.

Ouattara’s interest in extending his time in power may be, in part, to fend off an alliance between former presidents Henri Konan Bédié, 81, and Laurent Gbagbo, 75, representing the pre-Ouattara political order, which is preparing to compete for the presidency in 2020. The former leaders’ parties organized a major joint rally in Abidjan in August 2019 despite their lack of common ground. Bédié’s presidency in the late 1990s was marred by accusations of corruption and the invocation of xenophobia under the guise of “Ivorianness.” Gbagbo, meanwhile, remains in Belgium pending an appeal at the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity committed during the 2010-2011 electoral crisis sparked when he refused to step down after an electoral loss to Ouattara. The ongoing popularity of these former leaders reveals that ethnic and religious divisions in Côte d’Ivoire remain potent. Bédié and Gbagbo hail from the relatively more prosperous and Christian south, which has traditionally held power in the country to the exclusion of the more rural and largely Muslim north.

These divisions carry over into the security sector. Despite a major security sector reform effort in which nearly 70,000 ex-combatants were demobilized and competing militias integrated into the national army, divided loyalties persist. These tensions were evident in violent mutinies in 2016 and 2017. The prospect that the polarizing politics of the past may return has raised concerns that the reforms of the past 10 years may be undermined.

In short, despite commendable progress since 2010, the 2020 electoral process in Côte d’Ivoire will be a test of the country’s capacity to assert constraints on the executive, as well as of the depth of progress in advancing reconciliation, peacebuilding, and national identity. At stake is Côte d’Ivoire’s reputation as an economic and security anchor in West Africa.

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso

Presidential and Legislative Elections, November 22

Burkina Faso’s 2020 election will be dominated by the twin themes of security and democratic consolidation. Burkina Faso has experienced a rapid escalation of violent events involving militant Islamist groups in recent years. In 2019, it experienced 437 violent episodes involving extremist groups, resulting in 1,270 fatalities. This represents a four- and ten-fold increase, respectively, from the previous year. Hundreds of thousands have been displaced. By contrast, in 2014, Burkina Faso did not suffer from any such attacks. Fears that the violence could spread and engulf urban areas is worrying to many Burkinabe. Attempts by extremist groups to stoke intercommunal tensions, moreover, have frayed Burkina Faso’s long-cherished sense of national unity. The ineffective and at times heavy-handed response of security forces, which had not previously faced a serious security threat, has made leadership in the combating of militant groups an overriding concern for voters.

President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré (Photo: Koch / MSC)

The need for a more robust security response is unfolding at the same time that Burkina Faso is trying to build basic democratic institutions following the 27-year tenure of Blaise Compaoré. The 2020 elections will be the second democratic presidential and legislative elections post-Compaoré. Reforms under the current administration have involved proposals to reduce the concentration of power in the presidency and the dissolution of the elite Presidential Guard forces that sustained Compaoré’s tenure and subsequently attempted a coup. A constitutional referendum to formalize a two-term presidential limit that was originally planned for March 2019 is now expected in 2020. The slow pace of change is another point of frustration for the electorate.

Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was elected president in 2015 in a free and fair, if imperfect, election. He is running for a second term and will likely face a strong field of candidates. Given the still nascent nature of Burkina Faso’s democracy, political parties remain relatively weak organizations with limited national networks. The fluid context, volatile security environment, and evolving political institutions suggest there will likely be multiple twists and turns right up to the November elections, with an outcome that remains uncertain.

Ghana

Ghana

Presidential and Legislative Elections, December 7

The presidential elections in Ghana are shaping up to be the third act of the ongoing political rivalry between incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo of the New Patriot Party (NPP) and former President John Dramani Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC). Mahama won when the two ran against each other in 2012. Akufo-Addo returned to claim victory in 2016. The margin in the 2012 elections was particularly close, involving an appeal and a Supreme Court ruling to determine the winner. The election in 2020 is expected to be similarly close, focusing on sustaining the middle-income country’s continued economic development (averaging 6 percent annual growth), financial sector reform, control of corruption, equity, and job creation.

Despite the previous hard-fought campaigns, both political leaders distinguished themselves by working through the courts to adjudicate their differences—and ultimately graciously accepting defeat. These actions have set admirable precedents for how another close election would be handled. This cannot be taken for granted, however. Emotions can again be expected to reach a fever pitch, and all sides will need to exercise restraint and uphold buffers that prevent these emotions from spilling over into violence.

The process of democratic consolidation is a long one.… Progress cannot be taken for granted, lest previous gains be lost.

Ghana has a relatively strong set of institutions surrounding its elections that should strengthen these buffers. The Electoral Commission has earned a reputation as a credible and independent body, which has helped the competing parties accept the results as valid while reinforcing the legitimacy of the outcome. Ghana has an active civil society that has facilitated a culture of debate and dialogue among the competing actors. This has helped to focus the differences between the parties on issues of policy and vision, rather than personal attacks. Likewise, security actors (primarily the police, though with support from the army), working closely with the Electoral Commission, have gained valuable experience in protecting the electoral process in a professional, apolitical manner so as to facilitate citizen participation and safety.

Despite this institutional legacy, opposition parties have claimed that the NPP has been eroding the independence of the Electoral Commission and the courts. Recent years have also seen increased pressure on civil society and the media. In 2019, investigative journalists in Ghana have had their offices raided and have been detained and murdered—previously unimaginable actions in Ghana. Positively, 2019 also saw the passage of Ghana’s Right to Information law—the culmination of a two-decade effort to expand access to information from—and therefore improve oversight of—public institutions.

Ghana’s 2020 elections will be a test for the resiliency of Ghana’s institutions. It also stands as a reminder that the process of democratic consolidation is a long one—and that progress cannot be taken for granted, lest previous gains be lost.

Central African Republic

Central African Republic

Presidential and Legislative Elections, December 27

The Central African Republic (CAR) is one of Africa’s most fragile states, having faced persistent factional and intercommunal conflict since 2013. Thousands of people have been killed in the violence, and 1.2 million have been forcibly displaced. During this period, the economy has contracted by a third, making CAR one of the poorest countries in Africa, with a per capita income of under $300.

It is in this context that President Faustin-Archange Touadéra is seeking a second term in office. Touadéra’s election in 2016 was widely deemed credible. Moreover, political space for opposition groups and media has expanded under Touadéra. Former President François Bozizé returned to CAR on December 16, 2019, and may be a candidate under his party, Kwa na Kwa. The former president still has numerous supporters in the capital, Bangui, though he would likely be deeply opposed in rebel-held areas.

Working with a weak slate of security and justice institutions, Touadéra relies heavily on MINUSCA, the UN peacekeeping and stabilization mission, for security. In his effort to build an inclusive government that can bring peace, Touadéra negotiated a peace agreement in February 2019 that granted rebel leaders 13 ministerial positions and introduced Mixed Special Security Units (USMS) pairing government and rebel security forces. The move has precipitated anger and protests from some citizens and opposition groups who feel Touadéra is rewarding rebels for their destabilizing behavior. Although clashes between the armed forces and ex-Seleka coalition persist and arms continue to flow into the country from Sudan and Chad, violence has declined and humanitarian access has increased since the deal was signed. Nonetheless, the discipline and professionalism of the USMS remains highly tenuous and prone to politicization.

President Touadera with Russian President Vladimir Putin. (Photo: Kremlin.ru)

CAR is also at the center of geostrategic tensions. Russia has dramatically increased its engagement in CAR since 2018 with the deployment of 235 Russian security instructors primarily from the private military contractor, the Wagner Group. Wagner is also active in diamond and gold extraction efforts in rebel-held areas of the north. A Russian national, Valery Zakharov, now serves as Touadéra’s national security advisor, raising concerns over CAR’s compromised sovereignty. The Russian presence has been accompanied by an aggressive media campaign to tout the Russian contribution to security and disparage the UN and France, accusing the latter of attempting to recolonize CAR. CAR was also one of the eight African countries targeted by the Russian disinformation campaign exposed by Facebook where Russian-sponsored websites disguised as home-grown CAR entities would attempt to rally support for Russia.

Niger

Niger

Presidential and Legislative Elections, December 27

Niger seeks to take a major step forward in its democratic evolution with an election to determine who will succeed President Mahamadou Issoufou. Issoufou is completing his second 5-year term in office, and his stepping down will set a valuable precedent in Niger’s efforts to institutionalize this check on executive power.

The ruling Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism selected Interior Minister Mohamed Bazoum as its presidential candidate. Opposition leader Hama Amadou has returned to Niger after 3 years of exile in France. He hopes to contest this year’s election, though he must first clear some legal hurdles stemming from past criminal charges, which he claims are politically motivated. Seini Oumarou, leader of the National Movement for Social Development (the party of former President Mamadou Tandja), also plans to run.

Niger is undertaking this democratic transition while combating an increasingly aggressive insurgency from militant Islamist groups. Niger faced 78 violent attacks and 271 fatalities involving such groups in 2019—a three-fold increase from the previous year. Niger suffered the worst attack in its history on January 9, 2020, when 89 soldiers were killed in Chinagoder near the Malian border, an attack for which the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara took responsibility. This occurred just weeks after more than 70 soldiers were killed in a similar attack in Inates.

Leadership in times of insecurity, therefore, will be the central issue in this election—and one that may very likely overshadow the historic precedent of Niger managing a successful democratic succession.

Somalia

Somalia

Parliamentary Election, December

Long one of Africa’s most fragile states and facing Africa’s most active militant Islamist group, al Shabaab, Somalia’s parliamentary election scheduled for the end of the year will be a major test of its fledgling democratic process. The overarching political issue shaping the process is the tension between President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo and his vision of a strong central state and the constituent Federal Member States (FMS), which favor a more decentralized system of power sharing. The differences have frayed trust and resulted in declining levels of cooperation between Mogadishu and the outlying regions. Nonetheless, the negotiation presents an opportunity to address the fundamental governance conundrum facing Somalia in a highly decentralized and clan-based society. Key to the success of any agreement will be overcoming Somalia’s winner-take-all political culture that has led successive national governments to eschew compromise and attempts to build inclusive coalitions.

There are serious doubts over whether Somalia will be able to hold elections this year. Somalia needs to pass a new constitution, register voters, fund the polls, and create a legal framework on how to handle relations between Mogadishu and the FMS. Parliament is considering a new electoral law that would approve nationwide one-person one-vote polls (1P1V) instead of the old clan-based power-sharing formula. 1P1V is aimed at replacing the old system of clan-based power-sharing that was characterized by extensive vote buying, limited participation of women, and exclusion of marginalized and minority groups. The law would also require the elected president to nominate a prime minister from the party that wins the most seats in Parliament. Previously, the president was free to choose a prime minister independently.

Key to the success of any agreement will be overcoming Somalia’s winner-take-all political culture that has led successive national governments to eschew compromise and attempts to build inclusive coalitions.

Opposition groups are skeptical regarding a clause in the proposed electoral law that allows delaying elections and the government to remain in power until elections are held. This distrust is exacerbated by the fact that Somalia has no truly independent electoral commission, allowing the national government wide latitude to control the process. Meanwhile, in an innovation for Somalia, six opposition parties have formed a coalition, the Forum for National Parties (FNP), in order to broaden their appeal. The FNP is led by former president and leader of the Islamic Courts Union, which controlled Mogadishu in 2006, Sheikh Sharif Ahmed.

Insecurity poses another serious threat to the election. Al Shabaab was linked to over 1,300 violent episodes in 2019, resulting in close to 2,800 deaths. Al Shabaab remains well entrenched and controls large swathes of the country, meaning voter outreach and access will be limited. With a still weak security sector, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) continues to be an indispensable actor in providing security in the urban areas.

The Somali electoral process must also navigate the competition for influence by Gulf actors. A Cold War–style rivalry between the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia supporting the FMS versus Turkey and Qatar aligned with the central government has periodically played out in Somalia’s fractured political and economic systems, further exacerbating tensions. Somali politicians, meanwhile, have adroitly cultivated Gulf allies to earn millions of dollars by promising help to win contracts or by positioning themselves as candidates likely to win an election.

In short, the layers of complex challenges facing Somalia rightly temper expectations in the lead-up to the anticipated elections. To the extent that the central government and the FMS can use the occasion as an incentive to engage in a genuine dialogue on a functional power-sharing structure for Somalia, the process creates an opportunity to lay a stronger foundation for Somalia’s long-fragile state.

Joseph Siegle is Research Director and Candace Cook is Research Assistant at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

More on: Democratization Burkina Faso Burundi Central African Republic Côte d'Ivoire Ethiopia Ghana Guinea Niger Seychelles Somalia Tanzania Togo